It's three weeks into 2018, and I'm scared shitless.

We've filed all the paperwork. We've moved to Puerto Rico, and there's no turning back.

We're officially homeowners. We have a mortgage! In a hurricane-ravaged country, with businesses that depend on convincing people we're really great at what we do from thousands of miles away. We've sunk all of our savings into a gorgeous, needy, 200-year-old mansion in an uncertain housing market.

I'm told everyone feels really excited and a little bit nauseous when they buy their first house.

In addition to being scared, we're also thrilled. Some of you who know us or have been following along on our journey, know the latter half of 2017 hasn't been easy. After being hit by two hurricanes, we are exhausted. Scallywag is looking worse for wear. She's floating, and will be dreamy again one day, but for the moment, our boat home isn't liveable. And our paltry insurance payout means it will take a lot of our own sweat equity to get her back into fighting shape.

Jon and I decided, a few days into taking respite from post-hurricane rebuilding in our hometown of LA for a few weeks, that our plan to sail back to California just didn't feel like the right next move anymore. Despite everything, we missed Puerto Rico and all it offered us. And we wanted to make a permanent home there.

Why Puerto Rico?

We never planned to cruise full-time forever, but we also never want to give up on cruising. Working while traveling can be murder on you, physically, mentally and tax-return-ally. So we've been looking for a place to base ourselves during our entire trip from New York to Maine and back down. We found towns we fell in love with, but we just couldn't see ourselves staying there. And then we arrived here for hurricane season.

Puerto Rico, specifically San Juan, checked a lot of boxes for us:

-It is a friendly culture that welcomes new people

-It has a ton of great art and lively activities

-The food is killer

-It's beautiful and historical

-There are universities and art schools nearby (we realized all our favorite places had access to a great school.)

-It's near an ocean

-It's warm!

-The music is awesome

-It has a strong liberal and progressive community of locals and expats that we feel comfy in.

-It's still U.S. territory, which makes it easy to relocate our work, but feels like we live in a magical distant land with castles.

-There's an awesome tech community

-There's a major airport just 15 minutes away with cheap flights to lots of cool places.

-Real estate and cost of living is affordable and awesome

-Cell reception and internet are rock solid (when no hurricanes are nearby)

-It's a place where the money we spend matters and contributes to an economy that needs it.

Those are personal reasons we looked toward San Juan, but we can't talk about moving here without talking about how Puerto Rico has been in the news A LOT lately: For its booming tech scene, great tax incentives and its post-storm utilities nightmares. Also for the crypto bros who are moving in by the minute. And for its fight to become a state and the fight for decolonization.

The last few months have intensified all those stories. People are making real choices to commit or to leave.

As stalwart institutions fold, new ideas, businesses and newly arrived friends are also blossoming. In short, after the hurricanes, things are getting better here... and they aren't. There's a lot of awfulness to be had, and half the country is still without electricity. It's a strange, uncertain place to be at the beginning of 2018.

But it's an interesting place to be, and Jon and I decided we want our land life to be as dynamic as our sea-life is. This is a messy time to be here and not everyone's cup of tea. But for us, it seemed like a move that even if we completely failed with, we wouldn't regret.

So we did it.

The move from hell

Or at least we tried to. We began filing paperwork before the hurricane, and put an offer on our house just two days after Irma. It's taken all this time to finalize our new life here and walk through the doors of our new home.

For a lot of reasons -- hurricane outages, oddball personalities, sketchy bank lending practices, #islandlife -- every part of the process was difficult. While moving apartments about every two weeks for almost six months, we watched our paperwork get lost, our escrow fall through three times and everyone involved in our move and house purchase make money and make the process harder at the same time.

We thought we'd be able to move in by Thanksgiving, then Christmas, then never. It's a longer story for another post, but there was a day, Christmas eve to be exact, when we gave up. We packed up everything, made a list of everything we needed to do to fully exit Puerto Rico, and had a last teary drink to our dream of island life.

A few days before Christmas found us living in a cheap motel with everything we owned pulled from our leaky boat and stored in a rented minivan parked on the street outside.

One of our friends sent us a text: "Step back and make sure this house is meant to be your and Jon's next move! I hope it is bc it is awesome having you in PR, but shit, you should not be going through this!"

And at that point, we absolutely weren't sure that all the decisions we were making were leading us anywhere.

Looking back, it sounds silly and melodramatic, but the hurricane tore all of our life plans apart and at the end of 2017, we felt emotionally adrift.

Then, just two days before New Year's day, everything suddenly fell into place.

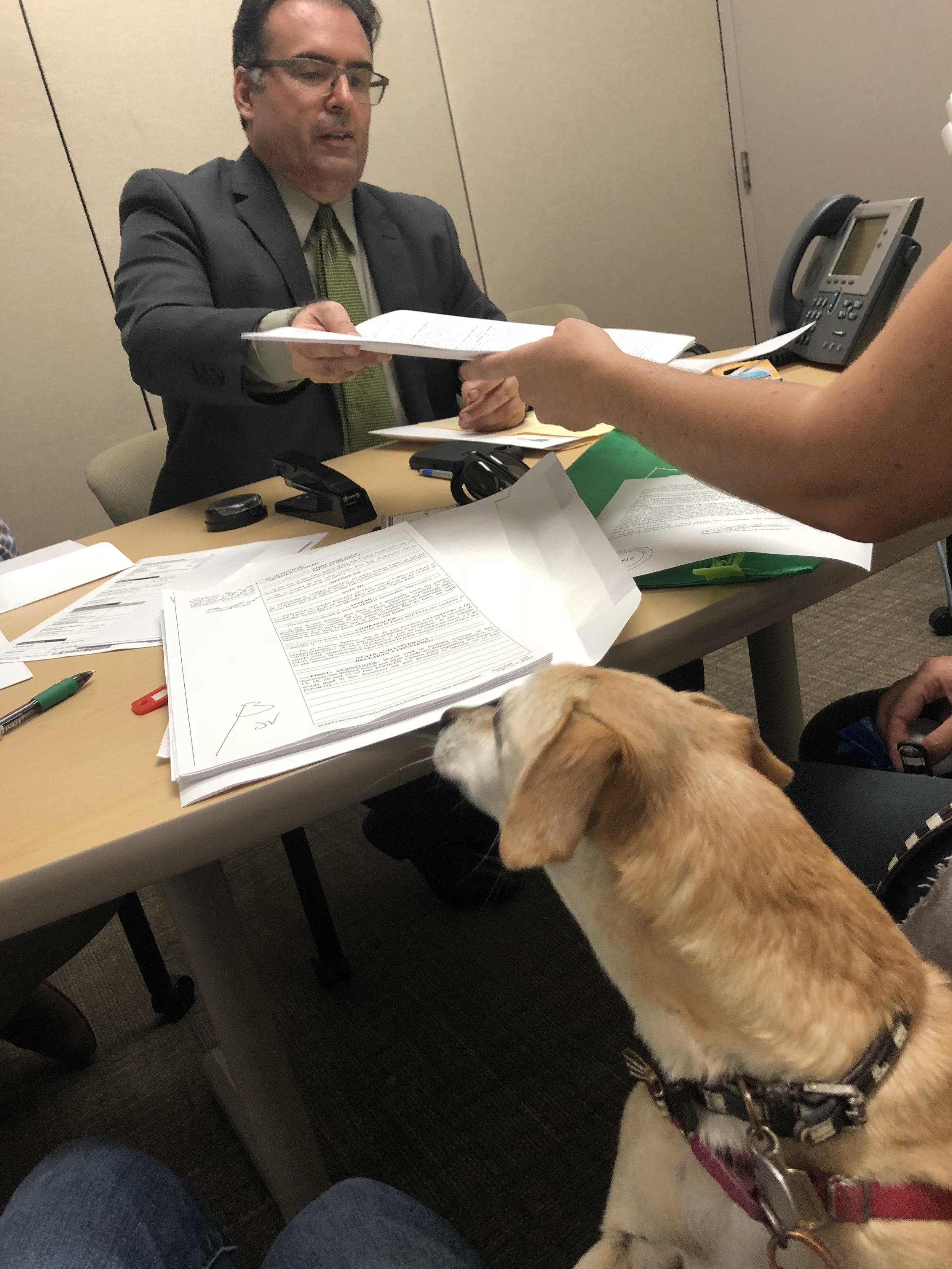

It was so sudden that we still had no place to live when we went to sign our mortgage papers. We had to take Honey to the bank with us.

I'm still shocked that it all came together. We are residents of Puerto Rico. We own a beautiful house in the Unesco World Heritage site of Old San Juan.

So what's the plan?

Our house is divided into two apartments that are exactly the same. Each have three bedrooms and a huge amount of living space. To say it's a change from our 200-square foot boat is a an understatement.

It's a mansion, built by one of Puerto Rico's first rum barons, 200 years ago. And it has some pretty cool features, including its own 36,000-gallon rainwater cistern. As soon as we recover from the down payment of our purchase, we plan to install solar panels on the ample roof, to bring it completely off the grid. It's not the tiny home we planned on, but we still hope to pursue the alternative lifestyle we've come to love.

We'll be living in the top floor and hosting guests on adventures from around the world on the bottom. In the longer term, I hope to make our home a site for movies, events and retreats.

My secret, lifelong dream has always been to be the next Gertrude Stein -- to be the ultimate host and curator of interesting people. I've always wanted to bring together great thinkers, artists and people with Big Ideas, introducing them to each other, and gently prod forward great work in a place that inspires it.

I know. That's a really lofty goal. More realistically, Jon has always wanted to invest in something that was more than just a home -- an investment and a place where he could practice the restoration skills we learned through #boatlife.

We both think we got the better end of the deal. (Here's a gallery from our Airbnb page.)

But, as I started off this post saying, it's terrifying. We've lived debt-free and relatively without responsibility for several years by living a tiny, off-the-grid life. Now we have a mortgage! And appliances! And a duty to others besides ourselves.

Business-wise it's also a risky proposition. We'll be running our home as a business, while investing even more in our own businesses (his/mine) that we've run remotely for years. The slow economy here means that our work has to remain top-notch and that we continue to receive the amazing referrals that have kept us going so far.

That's a big bet to take on ourselves and also that business in general will become increasingly global in the coming years. Luckily, we still strongly believe in both.

In the long run we hope to restore Scally back into top form and use Puerto Rico as our home base while spending several months a year sailing the Caribbean and nearby shores. We're taking our time on that one, because we know that no matter what, sailing will be a huge part of our lives, so there's no need to rush to get back out on the water.

What about the dog?

Yep, Honey definitely misses Scallywag. But the good news is our new home has some excellent sunny balconies that she's already staked out as her own. From little boat to cavernous mansion, she's the most adaptable animal we've ever met.